by AM | Nov 22, 2023 | Aggregate

Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft

On Monday, the Missouri Supreme Court rejected an appeal about how to word a ballot question on abortion in the state.

Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft had proposed asking voters whether they are in favor of allowing “dangerous and unregulated abortions until live birth.” The court rejected this wording despite the fact that this is factually correct. Democrats in the state want to push a new law that will allow unfettered abortion in this deep red state. The Democrats have had great success with this in several states so they are now pushing this in Missouri.

Missouri lawmakers have already banned abortion except in cases of medical emergency, but proponents of broader access to the procedure are seeking to put a question about it directly before voters next year. Democrats believe Missouri voters will allow abortion practices as radical as China and North Korea in the Show Me State.

Secretary of State Ashcroft promised on Tuesday to not stop fighting for Missourians to know the truth about the Democrat Party’s abhorrent abortion plans for Missouri

I will not stop fighting for Missourians to know the truth about this proposed abortion amendment! https://t.co/uCubweBle7

— Jay Ashcroft (@JayAshcroftMO) November 17, 2023

On Tuesday night The Gateway Pundit’s Jim Hoft spoke with Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft about this radical proposal by Democrats in Missouri.

Here is a partial transcript.

Jim Hoft: Can I switch topics now? There’s also quite a bit in the news about the Democrats – they want to vote on abortions in the state of Missouri. Can you give us a little bit more explanation of what the Democrats are wanting to do and your thoughts on that?

Jay Ashcroft: Yes. They have filed an initiative petition that would enshrine the right to abortion in the Missouri Constitution if they get enough signatures. And then the people of the state could vote it into the Constitution. It is an extremely far-reaching constitutional amendment. It would not return us to previous days of a Roe v. Wade world. It would allow abortion at any time for any reason – sex selection, because of the race of the child, you name it.

And it would prohibit any safety regulations or rules that really would protect a mother undergoing an abortion. It would not allow us to require that someone performing an abortion be a doctor or even a nurse or a paramedic or even a lifeguard that has CPR training from the Red Cross.

It would not allow any protection. It would not allow any civil or criminal penalties against a doctor that intentionally or accidentally hurt or killed a woman during the commission of an abortion. And I just think it’s very important that the people know what it would actually do so they can then make their own decision about how they want to vote on it.

Jim Hoft: I noticed that in some other states, they put abortion on the ballot, and they’ve done well in states like Michigan. But they’ve also put in some very radical pro abortion language that allows abortions up to the birth of the child. Is that what Democrats are trying to do here in Missouri, too, or is that not included in their proposal?

Jay Ashcroft: Yes, they are. I cannot imagine a more expansive abortion constitutional amendment unless it specifically required abortions be performed or paid for by the state government. The only thing that it doesn’t necessarily require is state funding, although some of them would seemingly require that if the state pays for other health care, it would have to pay for abortions. But that’s not as clean cut…

Jim Hoft: That sounds really scary then… Is there ways to prevent them from putting this on the ballot, or will it be on the ballot? And we just have to educate Missouri on what they’re actually voting for.

Jay Ashcroft: To get on the ballot, they have to collect roughly 180,000 signatures spread out among six of the eight congressional districts in Missouri. My understanding is that they’re collecting those signatures now. If they do not collect enough signatures, it will not be on the ballot. And I always caution people not to sign anything unless they read the whole thing. Pro life Missourians probably shouldn’t be signing any initiative editions. And if a pro life Missourian is asked to sign something outside of a business they like to go to, they can tell that business. They don’t appreciate the business allowing pro abortions to collect signatures. And that would make it much more difficult.

Jim Hoft: …It’s well known that the abortion laws in several states are as radical as they are in China or North Korea. We’re not talking about Western Europe where they have limitations on abortions. That never gets brought up. So do you think Missourians are aware of just how radical this is?

Jim Hoft: No, I don’t think so. Most Missourians are busy trying to work multiple jobs and figure out how to put paper gas in their car and food on the table. And I think it’s very important for people that are pro life that believe that the role of government is to protect those with no voice and no political power to get out and make the truth known about what this constitutional amendment would do. The courts have mandated language that really hides what this constitutional amendment would do. And you know that the people NARAL and Planned Parenthood will spend millions of dollars trying to make Missouri’s believe it’s just about medical freedom and not about committing abortion… And not just abortion, but abortion at any time during a pregnancy,.. And they’ll get away with it if people don’t understand what they’re literally…

…I frequently like to argue the absurd, to point something out, but this initiative petition were it the law, I hate to say this, It would actually allow coat hanger abortion.

Jim Hoft: Wow!

Jay Ashcroft: Something that used to occur and killed women and destroyed their ability to have kids in the future! We should not, as a state, go back to that sort of thing.

Jim Hoft: I agree. That’s a very strong statement, sir… Thank you for taking my call. I know you’re traveling tonight, so thanks so much. And happy Thanksgiving.

Jay Ashcroft: Happy Thanksgiving. Thanks for calling me. You helped my drive go by.

Here is audio from our discussion. Please note that Jay took our call while traveling across the state of Missouri.

The post EXCLUSIVE: Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft Tells Gateway Pundit – The Democrats’ Abortion Proposal Will Legalize Dangerous Hanger Abortions in Missouri (Audio) appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

by AM | Nov 22, 2023 | Aggregate

Anything goes.

U.S. District Judge Susan Paradise Baxter ruled on Tuesday that county boards of election may no longer reject mail ballots that lack accurate, handwritten dates on their return envelopes.

Judge Paradise Baxter was appointed by Donald J. Trump. So who was pushing this clown?

US District Court Judge Susan Paradise Baxter

George Behizy added, “This is yet another example of the Federal government telling a state how to run its elections. The power to oversee elections clearly belongs to state legislatures, not Federal courts, “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof” Article 1 Section 4 Clause 1.”

BREAKING: A Federal Judge in Pennsylvania has ruled that undated mail in ballots can be counted in the 2024 election despite a state law that clearly prohibits it. This means mail in ballots with no dates or incorrect dates will be counted

This is yet another example of the… pic.twitter.com/Ij8DO8y5mX

— George (@BehizyTweets) November 22, 2023

The AP reported:

Mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania without accurate handwritten dates on their exterior envelopes must still be counted if they are received in time, a judge ruled Tuesday, concluding that rejecting such ballots violates federal civil rights law.

The decision has implications for the 2024 presidential election in a key battleground state where Democrats have been far more likely to vote by mail than Republicans.

In the latest lawsuit filed over a 2019 state voting law, U.S. District Judge Susan Paradise Baxter ruled that county boards of election may no longer reject mail ballots that lack accurate, handwritten dates on their return envelopes. Baxter said the date — which is required by state law — is irrelevant in helping elections officials decide whether the ballot was received in time or whether the voter is qualified to cast a ballot.

The GOP has repeatedly fought in court to get such ballots thrown out, part of a campaign to invalidate mail-in ballots and mail-in voting in Pennsylvania after then-President Donald Trump baselessly claimed in 2020 that mail balloting was rife with fraud.

The post Trump-Appointed Federal Judge in Pennsylvania Rules Undated Mail-In Ballots Can Be Counted in 2024 Election appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

by AM | Nov 22, 2023 | Aggregate

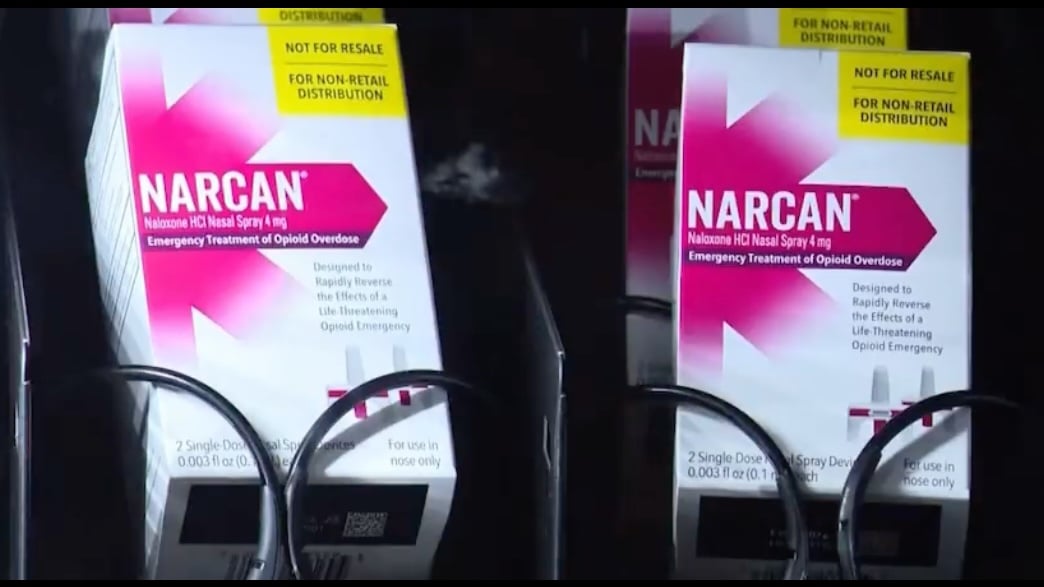

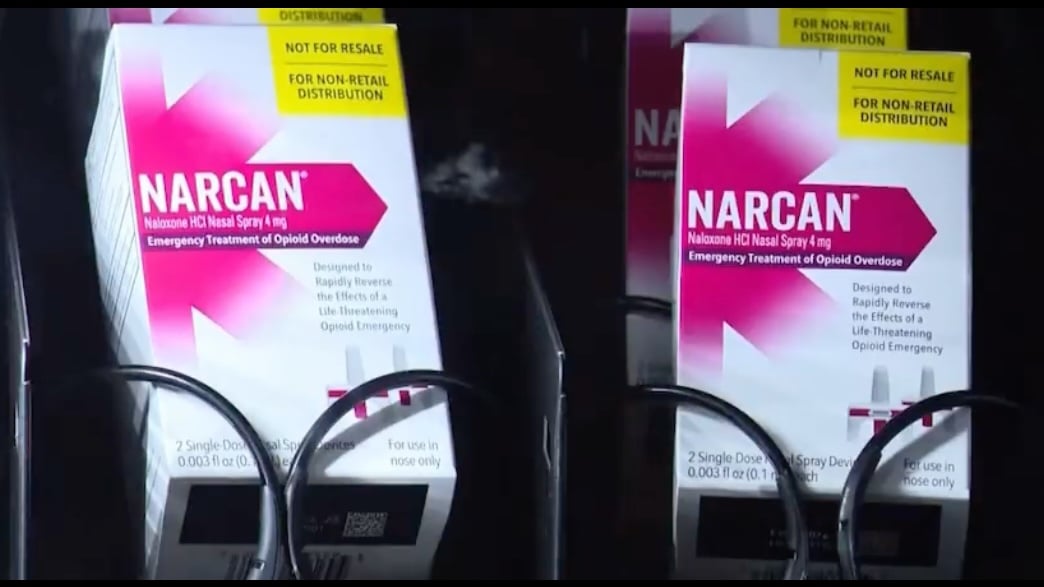

The Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office has installed a Narcan vending machine inside of its Detention Center’s lobby.

The new Narcan vending machine is currently siting next to a Coca-Cola machine and will be available to the general public 24/7.

Narcan is a life saving drug that is capable of reversing an opioid overdose when its used properly.

During a recent news conference Mecklenburg County Sheriff Garry McFadden touted the new vending machine and stated, “How about we give out Narcan instead of turkeys this year.”

Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office unveils new Narcan vending machine aimed at reducing overdose deaths https://t.co/mLf4D5q1ZO

— WCNC Charlotte (@wcnc) November 22, 2023

Per WSOC-TV:

The Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office is making a life-saving medicine available for free, and you don’t even need to talk to anybody in person to get it.

The sheriff’s office debuted a special vending machine filled with Narcan this week.

The machine is in the arrest processing center, but anyone can get Narcan there for free.

Narcan is a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose and save a life. That’s why the sheriff’s office recommends everyone carry it, whether they use opioids or not.

McFadden doesn’t just want Narcan vending machines inside the Sheriff’s Office but he is also advocating for them to be placed in schools.

McFadden stated, “Narcan should be stocked in nightclubs, schools and businesses. It should be as common as having a bottle of Tylenol or Advil on hand.”

Mecklenburg County, Sheriff’s Office Installs Narcan Vending Machine In Jail, Schools Could Be Next pic.twitter.com/MC44UIg9Ck

— Anthony Scott (@AnthonyScottTGP) November 22, 2023

North Carolina isn’t the only state with Narcan vending machines, New York has installed vending machines that contains both Narcan and drug paraphernalia.

READ:

UPDATE: NYC Vending Machine Offering Free Drug Paraphernalia and Narcan, Emptied Within 24 Hours

The post Sheriff’s Office in North Carolina Installs Narcan Vending Machine, Sheriff Says Schools Are Next appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

by AM | Nov 22, 2023 | Aggregate

The Soviet Sixties, Robert Hornsby, Yale University Press, 675 pages

When the coup plotters overthrew Nikita Khrushchev on October 14, 1964, springing their trap at a meeting of the Presidium with a motion to strip him of all his party and state posts, Khrushchev went willingly. His son Sergei recalled his father grumbling when he returned home that night: “I am old and tired. Let them cope by themselves.” Nothing like this could have happened to Stalin, Khrushchev added, but now “the fear is gone and we can talk as equals. That’s my contribution. I won’t put up a fight.”

Had things really changed? Was the Soviet Union in the 1960s and ’70s a freer country? Yes, argues Robert Hornsby in The Soviet Sixties. The book fills a gap in the average American’s understanding of the history of Communism, which generally skips straight from purges to perestroika. There was a long period in between when the Soviet Union was not the groaning, dysfunctional gerontocracy of recent memory. The standard of living was lower than in the United States but improving rapidly. The two Cold War powers seemed evenly matched. No one was afraid of the midnight knock on the door anymore.

The Sixties in the Soviet Union began with Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” on February 25, 1956. By acknowledging Stalin’s crimes, it signaled the start of a more open era. Amazingly, the speech could easily have gone very differently or not been given at all. When Khrushchev proposed the idea, many Presidium members said it was a bad idea, some because they sincerely did not think Stalin deserved execration, others because they worried it would undermine their own position since they had all served Stalin during the period in question. They urged Khrushchev to postpone the speech until more historical research could be done or to leaven his criticism with praise for Stalin’s accomplishments. It was Nikolai Bulganin who backed up Khrushchev and said he must give the speech as intended, because “party members could already see that the attitude toward Stalin had changed” and “it would look cowardly not to raise the issue.”

There was still oppression in the new era, but nothing like the bad old days. Hornsby gives the number of prosecutions for counterrevolutionary crimes per year: In the late 1940s, the average was 100,000; in the early 1950s, 40,000; in 1954, 2,000; in 1955, 1,000; in 1956, 400. In 1957, during the last big crackdown on dissent, it ticked back up to 2,000, but “less than 2 percent were jailed for ten years or more; and nobody was executed.” There was also none of the deranged paranoia from the top that had characterized the Terror. Under Khrushchev, Hornsby says, “convictions were seemingly rooted in concrete events that had actually happened, rather than in invented conspiracies.”

People who made off-color jokes about party leaders in the workplace were not sent off to the gulag anymore. They were instead given the profilaktika (phrophylaxis) treatment, which came in two forms. “Open” prophylaxis meant your workplace or your apartment block would bring up your error at a public meeting, give you a chance to apologize, and offer suggestions for improvement. “Private” prophylaxismeant the local KGB would invite you for a chat, warn that they were watching you, and explain the consequences of continuing on your path. “The use of intimidation from officialdom (rather than outright repression) and social pressure from the wider public were to be at the heart of this new approach to tackling the erring citizen without branding them ‘anti-Soviet’ at the first sign of trouble,” Hornsby writes. Perhaps it did work. According to the KGB, “the majority of those subjected to prophylactic measures did not offend again.”

All of this mellowing took place under an unlikely reformer. Khrushchev was, after all, a former protege of Stalin. He was also very stupid. He once gave a speech in Tashkent praising the wonderful Tajiks in the audience for their success in growing cotton, which they were doing much better than those lazy Uzbeks next door. An aide had to quickly tell him that it was actually Uzbeks he was talking to. But Khrushchev’s impulsiveness had its upside. If something struck him as a good idea, he would do it, without thinking too much about how to rationalize his decision ideologically. That was how Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn came to publish his camp novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in the literary journal Novy Mir in November 1962. Khrushchev bypassed the censors and gave the editors his personal permission.

Most Russian liberals were still determined to work within the system. The Soviet Union had many flaws, they reasoned, but these would be corrected through reform, not by overthrowing the government. In contrast to American and European campuses during this period, university students did not riot or declare their government illegitimate. The only campus unrest Hornsby mentions involved students from the Third World. Twenty Nigerian university students brawled with their Russian peers in Leningrad in 1964 “after months of escalating tensions had gone un-addressed.” A Ghanaian student named Edmund Assare-Addo was found dead in a gutter in Moscow in December 1963, and friends claimed he was knifed to death by a Russian who resented his pursuit of Slavic women (Russian authorities said the victim passed out drunk in the snow). Five hundred African students gathered in Red Square to stage a protest against racism, drawing the attention of the Western press.

For the average Russian, the Sixties had nothing to do with the treatment of dissidents, of whom there were very few. The story was rising living standards. One million Russian households owned T.V. sets in 1955. It was 10 million by 1963 and 25 million by 1969. The number of people working in the retail sector doubled over the course of the decade. Some of this was a conscious choice by party leaders to reorient the economy toward consumer goods. Some of it was having more prosperity to go around in the first place: between 1961 and 1969, the first Siberian oil deposits were tapped and Russia became a net exporter of oil.

The space race was competitive, with the Soviets beating America into orbit with Sputnik in 1957 and then sending the first man into space with Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961, a date still celebrated today in Russia as Cosmonautics Day. When Yuri Gagarin returned to earth, he landed hundreds of miles off course in the Saratov Oblast and had to hitch a ride with a peasant woman on a horse-drawn cart to find a telephone. Something about that juxtaposition, captured in a famous photograph, conveys the essence of the Soviet Sixties: the old world of the village and the new world of space travel joined in a common enterprise, making their ramshackle way into the future.

Something else the Gagarin episode captures is the self-confidence Russians felt during the Sixties, to an extent rare in their history and not just the Communist period. Hornsby quotes a computer programmer who remembers the high quality of Russian technology under Khrushchev but sighs, “We made our last good computer in 1962.” As Hornsby explains, the decline was the result of “opting to copy Western blueprints, rather than producing home-grown designs.” This echoes something American scholar Donald Raleigh records in his oral history of Soviet Baby Boomers. One interviewee tells him that, under Brezhnev, “You’d come with an idea, let’s say, and the first question that arose was ‘And over there in the West? Do they have this? If they don’t have it, then why do we need it?’ Under Khrushchev this question never arose.”

Every country ought to feel that kind of self-respect, even our enemies, even those that operate under evil systems of government, as Communism surely was. Reading about Russia’s reforms and successes during the period in Hornsby’s book, I did not find myself, as a reader, rooting for them to win the Cold War. Yet I did not want them to hurry up and reach the cultural cringe of the 1980s when they felt they could do nothing right, either.

To close with a personal anecdote: When I gave birth to my youngest son, the delivery room nurse happened to be from Belarus. We started talking about Slavic matters, since my husband is Russian, and I made a joke about going into labor so close to Cosmonautics Day and how if the baby had arrived a few days earlier, I would have had no choice but to name him “Yuri.” As soon as I said it, I felt like an idiot, because I had no idea whether Cosmonautics Day is taken seriously in Belarus or regarded as a relic or a joke. To my surprise, the nurse nodded with great seriousness, “Yes, Cosmonautics Day.” And then after a long pause said, “He was a great man.”

How strange, I thought, to have a new holiday on the calendar that commemorates one of your country’s great accomplishments instead of some historical sin like slavery or indigenous genocide. In the totally unironic way this woman spoke of Gagarin’s greatness, I detected honest civilizational pride. There were many things in Hornsby’s book that reminded me of the country I live in today, including ideological profilaktika. That pride was the biggest difference.

by AM | Nov 22, 2023 | Aggregate

Vivek Ramaswamy says he wants to “make hard work cool again.” The long-shot Republican candidate has been visiting places GOP politicians typically avoid, like college campuses, preaching the supposedly countercultural virtue of toil. His messaging won’t win him the nomination, much less address the crises of the American labor market. Yet they are a striking reminder of the stability of Whig ideology in our political life across nearly 200 years.

Whig ideology—or “the Whig Counter-Reformation,” as Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called it—denies the existence of enduring social classes in the United States, or else suggests that there are no enduring conflicts between the classes. Social misery is the product of either rare misfortune or the failure of indolent individuals to seize opportunity. And reform isn’t a matter of redressing imbalances in power through politics. No, it’s the heart or “the culture” that has to be reformed. Hard work has to be made “cool again,” as Ramaswamy says.

In framing things this way, Ramaswamy stands in an old tradition. Whig ideology was the response mounted by America’s market elites to the Jacksonian uprising. For decades since the Founding, America’s market system had chugged along, industrializing the economy, proletarianizing its once-independent working men, and imposing enormous new stresses on the yeomanry. But it wasn’t until the crash of 1819 that the frustrations of the many, and their sense of vulnerability relative to the few, congealed into what then–Secretary of War John C. Calhoun described memorably as a “general mass of disaffection.”

Not unlike Donald Trump in 2015-16, Andrew Jackson was the unlikely outsider who gave voice to the disaffected. His 1824 presidential bid began as a ruse by local oligarchs against their enemies in his native Tennessee but soon resonated nationally. Old Hickory, who had been left in debt by his own failed stint as a land speculator, blamed paper money and banks for the people’s suffering. Blocked by the “corrupt bargain” between John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay in 1824, Jackson clinched the presidency four years later. His anger soon found a more specific target in the imperious Second Bank of the United States. The BUS was a private, profiteering institution that was chartered and partially funded by Congress but that strenuously resisted democratic control. This, although it effectively acted as a central bank and disciplined the flow of credit by buying and holding—or selling and demanding specie for—the paper notes of much weaker state banks.

Jackson’s anti-Bank message resonated with broad ranks of American society (although the exact share of the population that supported Jackson’s Bank War has long been contested by historians). Western and Southern smallholders, urban workers in the North, and smaller capitalists everywhere who felt excluded by the establishment rallied to the Jacksonian cause, as did reformist intellectuals like Orestes Brownson, George Bancroft, William Leggett, Frances “Fanny” Wright, William Cullen Bryant, and so on.

Jackson’s “solution” to the tyranny of the BUS was small government: Another old pattern in American history is the libertarian conviction that often goes hand-in-hand with populist sentiment. Jackson, while in some respects an expansive nationalist, was in others a Jeffersonian strict constructionist. He had long believed that “the congress has no constitutional power to grant a charter…of paper issues,” as he told his Democratic senatorial ally (and one-time duel opponent) Thomas Hart Benton. So he vetoed the Bank’s charter when it came up for renewal, and then proceeded to remove federal taxpayer funds from its coffers, placing them instead in select state banks, the so-called pets.

For our purposes, the substance of Jackson’s reforms in the Bank War matters less than the reaction they elicited from market elites jittery about the rise of democracy, both political and economic. Save for a few pseudo-aristocratic strongholds like Rhode Island and South Carolina, the franchise had in this period expanded to include many formerly excluded ranks of white men. A people grown accustomed to having a more direct say in political matters also increasingly demanded popular control over market institutions: not just banking and the currency, but also the workplace became a site of political contestation through the rise of the labor movement.

It was against this backdrop that Whig ideology began to take hold among the wealthy and upper middle classes. An earlier generation of old-school Federalists—men like Chancellor James Kent, Noah Webster, and, yes, Alexander Hamilton—could simply insist that the rabble have no business shaping policy. As Noah Webster wrote, if distinctions between rich and poor were to endure, and they always would, then why not recognize them in the structure of the state? For “the man who has half a million of dollars in property…has a much higher interest in government, than the man who has little or no property.” The one deserves a much greater say than the other.

Yet by the 1830s, Jackson and the Jacksonians had made it impossible to speak this way. One sign of the change came in 1834, when Roger Brooke Taney, among the most militant Jacksonians in Old Hickory’s Parlor (as opposed to “Kitchen”) Cabinet, returned to his home in Baltimore, having helped the general slay the banking “monster” as his Treasury secretary. The local pro-Bank organ, the Chronicle, mocked the working classes who turned up to greet Taney. Their horses, the paper noted, bore collar marks on their necks—meaning, these were poor people with humble livestock.

Democratic papers naturally took advantage of the misstep and, as usual, counterpunched twice as hard. If the Chronicle’s reporter had examined the hands of the men riding the work-worn animals, bellowed the Jacksonian Republican, he would have noticed the same “striking indications of work as were witnessed on the necks of the horses.” It added: “We had reason to believe that our neighbor had but little regard for ‘working men,’ but did not suppose the antipathy went so far as to ridicule a procession on account of the employment in it of working horses.” The Chronicle’s class arrogance was downright ridiculous in this new age.

Yet the elites would soon master a different political vernacular, and this was the Whig ideology. Partly, it had to do with how Whig politicians presented themselves. Going forward, even politicians representing market elites would have to pitch themselves as men of humble origins, solicitous, above all, for the happiness and prosperity of other Americans from such backgrounds. The Whigs would master this transfiguration by 1840, embracing their nominee William Henry Harrison’s dubious image as a downhome man of the people. What Jackson dismissed privately as the Whigs’ “Logg cabin hard cider and Coon humbuggery” would prove thoroughly winsome at the ballot box, to Old Hickory’s chagrin and that of his Democratic successor, Martin Van Buren, who was swept out of office that year.

But beyond campaign imagery, there was a deeper ideological effort afoot. Gone was the old-school Federalist idea that those with property should have greater say in the affairs of state. Instead, the Whigs promoted the idea that we shouldn’t think of class differences at all, since “the interests of the classes [were] identical,” as Schlesinger noted. A prominent Philadelphia Whig, for example, wrote that “however selfish may be the disposition of the wealthy, they cannot benefit themselves without serving the labourer.” Thus, “if the labouring classes are desirous of having the prosperity of the country restored”—this was in the aftermath of the Bank War—“they must sanction all measures tending to reinstate our commercial credit, without which the wealthy will be impoverished.”

A step further was the idea that America simply has no social classes at all. Wrote one Whig critic of the labor movement: “These phrases, higher orders, and lower orders, are of European origin, and have no place in our Yankee dialect”—seeming to forget his own ideological forebears’ insistence that there are, in fact, rich and poor, and that the former must be allowed to rule unchallenged.

Still another variation was to suggest that social classes in America are so fluid and mobile as to be politically meaningless. Today’s worker is tomorrow’s capitalist, who hires a hand, and this third will tomorrow own his own shop and hire still other workers. And so on. “The wheel of fortune is in constant operation,” wrote the Whig Sen. Edward Everett, “and the poor in one generation furnish the rich of the next.” The Whig minister Calvin Colton agreed: “Every American laborer can stand up proudly, and say, I AM THE AMERICAN CAPITALIST, which is not a metaphor but literal truth.” Abraham Lincoln, too, promoted this idea — which I have elsewhere called the cycle-of-classes theory of political economy — in his famous Speech to the Wisconsin Agricultural Society.

Yet the most powerful element of Whig ideology was the primacy of internal, spiritual, or cultural uplift over governmental policy or material reforms. The worker will rise, wrote the Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing, not by “struggling for another rank,” nor through “political power,” but by “Elevation of Soul.” Instead of seeking worldly reforms, Channing advised, workers should grow in “intelligence” and “self-respect.” Another Whig reformer declared: “Legislation can do nothing; combinations among working classes”—that is, labor unions—“could probably effect no permanent remedy.” But if workers bettered themselves interiorly, they would find the peace that no external policy solution could bring.

“Making hard work cool again” harks back to these old Whig themes. For it suggests that a significant share of American workers simply decided to stop participating in the labor market or grew tired of making productivity gains. The problem, in this telling, aren’t things like the loss of U.S. manufacturing thanks to neoliberal trade policies and the rise of a low-wage and precarious services-based economy. Nor is the financial industry’s erosion of the real economy to blame. No, American workers just decided, en masse, that work is un-cool, and it’s up to the Whiggish politician to tell them that work is pretty cool, actually.

Nearly 200 years ago, Orestes Brownson, the Massachusetts preacher, journalist, and Jacksonian reformer, who certainly wasn’t one to pooh-pooh spiritual uplift, answered Whig ideology once and for all. “This position,” he countered,

is not tenable. If it were, it would be fatal to all progress, and be most heartily pleasing to all tyrants. The plain English of it is, perfect the individual before you undertake to perfect society make your men perfect, before you seek to make your institutions perfect. This is plausible, but we dislike it, because it makes perfection of institutions the end, and that of individuals merely the means. Perfect all your men, and no doubt, you could then perfect easily and safely your institutions. But when all your men are perfect, what need of perfecting your institutions? And wherein are those institutions, under which all individuals may attain to the full perfection admitted by human nature, imperfect?